What Yvonne Rainer taught me about experimental game design

All the turbulence around games and the increasingly diverse range of opinion on what is or isn’t a game, and what does or doesn’t constitute game development leads me to a fairly basic question:

What do we mean when we talk about game design?

Is it the design of spaces of possibility defined by the mechanics and fueled by the goals to which they are applied?

Is it the use of participatory storytelling to deliver personal narratives?

Is it something more ethereal, like the creation of potential emotional states?

Is it a tool for self-exploration and expression?

The more diverse games become, the harder it is to see one “game design” that unites them all. As we’ve cycled through a variety of movements from artgames to notgames to queer games to altgames, each has brought its own claims on the medium of games, and in turn caused reactionary territorial defensiveness. Artgames suggested games could be more than entertainment; notgames challenged that games had to be competitive, goal-oriented and mechanically rich; queer games brought a whole new set of values, perspectives and stories to games; and most recently, altgames question the assumptions of what indie means, and how games can be a sustainable medium. With each of these, particularly the latter two, there are always power politics at play over whose voices are heard and celebrated, and who has access to infrastructure and thus audiences and resources. But in all four of these cases, considered from a practitioner perspective, these debates come down to what we mean when we talk about game design.

A couple weeks ago, I found a handle to these questions in an unexpected place: the minimalist choreography of Yvonne Rainer and her colleagues in the experimental dance world of early 1960s New York. Under the guidance of the dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, the musician and choreographer Robert Dunn and the musician and artist John Cage, dancers, filmmakers, musicians, writers and other artists explored what lay beyond the current state of dance. Rainer and the group of like-minded practitioners formed the Judson Dance Theater as a stance against the then-dominant modern dance typified in the work of Martha Graham. Though a departure from traditional ballet in subject matter, costume, set design and many other ways, Graham’s canonical modernism, typified in “Appalachian Spring,” also stayed firmly inside the boundaries of dance—highly stylized movement distinct from the movements of everyday life, the repetition of forms and movements, an overt sense of drama, designed to accompany melodic scores, among other similarities.

Graham’s choreography represented all the problems with dance for Yvonne Rainer. To express her ideas, Rainer wrote the “No Manifesto”:

No to spectacle.

No to virtuosity.

No to transformations and magic and make-believe.

No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image.

No to the heroic.

No to the anti-heroic.

No to trash imagery.

No to involvement of performer or spectator.

No to style.

No to camp.

No to seduction of spectator by the wiles of the performer.

No to eccentricity.

No to moving or being moved.

Though it might seem otherwise, these ideas were not anti-formal; in fact, they were the opposite. They were deeply concerned with dance as a cultural form, despite the rejection of the pervading aesthetic of the time. Rainer sought to re-locate the intent of the choreographer from the traditions of dance as a professional practice isolated from life to what she called “ordinary dance.” This wasn’t a dismissal of dance as a medium; it was a reassessment of dance as a more-human scale medium concerned with the movement of the body and not the baroque, contrived movements of previous dance traditions.

At the heart of Rainer’s work is the question of intent: what does it mean to choreograph dance when so many of the traditions no longer apply?

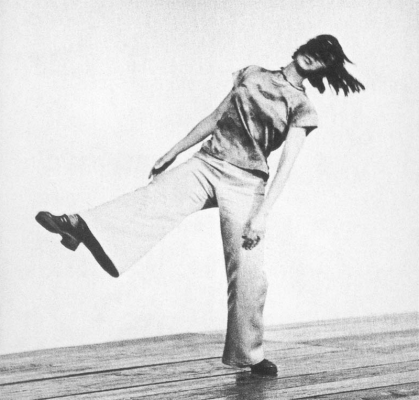

The embodiment of these beliefs are found in “Trio A,” a minimalist dance choreographed in 1966, shortly after the manifesto was written. The six minute dance is made up of a sequence of non-repeating movements that draw on the movements our bodies make in the process of work, play and the mundane. Everyone had a virtuosity with these movements, but a virtuosity developed through living, and not through art.

“Trio A” had style—an anti-style, but a style, nonetheless. Walking, swinging arms idly, hopping, slouching shoulders, rolling over—the movements and gestures that we perform on a regular basis without a second thought—were invested with new meaning, a treated as the elements from which dance could be composed. The style emerged from the choices Rainer made in picking gestures and movements, and how they were sequenced together. The flatness of the dance is also a stylistic choice—to remove intonation and bombast, and replace them with quiet execution.

There was a craft here, too, without question—Judson dancers were notoriously rigorous. But it was toward a different end. It was just not the craft of precise execution of moves drawn from the formal canon of modern dance. It was a craft of seeing and thinking in new ways, and de-training the dancer to move in a new way, to consider a less adorned form of performance. It was a craft informed by art, writing, music, philosophy and many other external influences.

The dance establishment of the time—Martha Graham and other modernists—looked at Rainer and her performers and didn’t see dance at all. I think this is what people used to traditional games, and thus game design, think of when they look at altgames and queer games and notgames: some people standing around in a box and calling it a game. Though it has become something of a dirty word, these are formalist contestations around form, intent and craft.

Let’s pause for a moment and consider these three terms. Often a talisman used to trigger consternation amongst game developers and critics alike, form is just another word for medium: painting, sculpture, film, music, games. Intent speaks to what the artist wants to do with the medium: make money, express themselves, solve world hunger, participate in an ongoing dialog with other practitioners, etc. Craft then is the set of skills necessary to produce work within the given medium that meets the artist’s intentions.

When we talk about game design (or choreography) we are talking about the interplay of these three concepts. We all make assumptions around these, often in the context of our own values and tastes. Pervading opinions take hold and color the way we think about games and their design. Even (especially) indie games are prone to this, setting expectations for experimental approaches to gamemaking.

Indie gamemakers bring a particular set of sensibilities to the form of game, the most dominant being that when we say game, we really mean videogame. Along with this come the privileging of visual polish, mechanical representations of systems, play experiences polished through playtesting, among others. Chris Hecker’s Spy Party and Capybara Game’s Super Time Force represent two examples of this perspective on the form of games.

Along the margins, we see something quite different: personal expression, expanding the range of people who can see themselves in the games they play, pursuing stories drawn from life and fantasy rather than make believe. These lead to radically different kinds of games: Porpentine’s Howling Dogs and Liam Burke’s Dog Eat Dog, for example, that suggest new possibilities for games.

Artistic intent is realized through making, and making requires craft. Now, questions of craft come up with too much frequency around artgames and notgames and queer games and altgames. Certainly, many of the gamemakers within these loose communities of practice do seem suspicious of or uninterested in virtuoso gamemaking, at least in the traditional sense of programming, modeling photo-realistic worlds and game systems brought to a fine sheen through playtesting. That said, there is a deep sense of craft in artgames, notgames, altgames and queer games—on writing, on finding ways to express feelings and ideas that simply haven’t been done before with games, on making games out of “ordinary tools” like Twine or Gamemaker or the other more affordable and accessible tools, on exploring the possibilities of 3D worlds unburdened of guns, puzzles and loot.

We find Twine games like anna anthropy’s Queers In Love At The End Of the World—a 10-second Twine game contemplating the decision of how to engage with one’s partner at the edge of time. While its production wasn’t burdensome, the ideas and experience are nonetheless well-crafted and powerful. Or Robert Yang’s under appreciated Intimate, Infinite, a Unity-built meditation on Borge’s “Garden of Forking Paths.” The game has many of the trappings of a “AAA Indie” production—lush 3D environments, cinematic camera work, cut scenes—but the ways players engage is more cerebral, and less interaction-based.

Like Rainer, there is a certain re-training or de-training at play in these games. But there is also a shift away from the traditions of game development toward the craft skills of other mediums—writing, ‘zine-making, literature, theater, poetry, to name a few. So perhaps instead of de-training, it is better to consider altgames as a reimagining of game design.

All of which comes back around to the form of games. In order to realize the intentions and create new kinds of play for a new audience, games and their design must be reimagined around the intent of the artists, not the expectations of the players. From this broaden perspective, we comfortably locate Squinky’s Coffee: A Misunderstanding and Merrit Kopas’ Hugpunx inside our reimagined understanding of game design.

Rainer’s minimalism, once considered far removed from dance, is now an important pillar in the history of dance. But it took time and dedication. They were continually denied access to the world of modern dance because they didn’t seem to be creating or performing what passed for dance at the time. This put them outside the cultural, social and economic infrastructure of the dance community. So Rainer and her cohorts looked beyond dance for inspiration, and made their own space—the Judson Dance Theater—where they put on free or affordable performances and workshops.

Ultimately, by questioning the form of dance and what it means to choreograph, Rainer expanded the medium. Will the same be true of queer games and notgames and artgames and altgames? One thing is for sure: questioning what constitutes game design is essential to the medium of games, even if it feels like rejection to some, because it broadens the medium for us all.

Boris Willis

Thank you for this thoughtful and insightful piece. I work in both dance and game design and recently wrote about this subject. I am inspired to do more.