The following essay is based on a talk I gave on February 6 at College Art Association’s annual conference. It was part of “The Visual Politics of Play: On the Signifying Practices of Digital Games” organized by Soraya Murray. My talk wandered off the panel topic a bit, looking more at the challenges of critiquing games that fall outside traditional gameplay expectations.

—————–

Over the last few years, I’ve increasingly felt the need for a more inclusive aesthetic framework for considering videogames. More specifically, I seek an aesthetics that takes into account play experiences that go beyond typical player expectations: the pursuit of goals, the exploration of the space of possibility in a game, and winning, and so on. Some of this thinking is captured in my book, Works of Game, released last year, and Fun, Taste & Games, a book I’m currently writing with David Thomas.

Today, I would like to set out on a new path within this project—exploring evaluative approaches for games where the play emphasizes sensory, thematic or affective experiences that bend and break videogame tropes. I’ve picked three games to use as case studies today—Tale of Tale’s Sunset, Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero and Eddo Stern’s Vietnam Romance. In each case, the gamemakers combine videogame technologies and game design tropes with literary, film and visual art strategies to create sensory-driven play experiences.

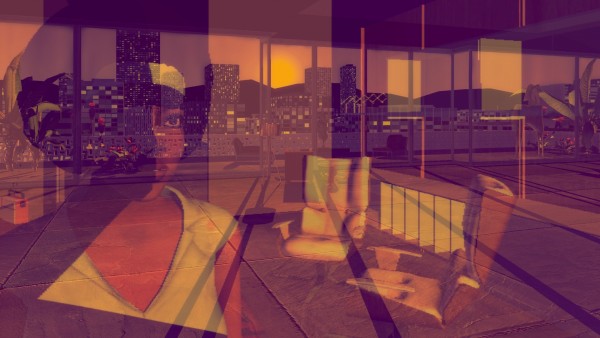

Sunset

First, Tale of Tales’ Sunset from 2015. The player guides Angela, an ex-pat African-American woman living in a Latin American country roiled in civil war. Her job is your job: housekeeping for a wealthy man. The game consists of 44 late-afternoon visits to the apartment. Each day, Angela is given a set of tasks to accomplish—unpack a box, clean the kitchen, wash windows, vacuum the floor. The player has until the sun sets each day to complete her tasks. At the end of the visit, Angela returns to the elevator, and the game advances to the next housekeeping appointment.

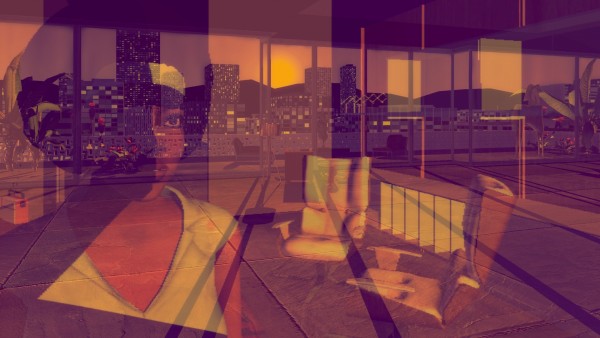

The game is played from a first-person perspective, meaning we never really see Angela outside her reflection. We never see the owner of the apartment either, leaving the apartment itself and the city outside its windows as the primary visible characters. The carefully-designed and decorated 70s bachelor pad Angela maintains is represented in a “videogame realist” style balanced between game engine realism and a sculptural stylization just this side of the uncanny valley. The environments and objects—pillows, plants and rugs alike—all have that hard-surface look of 3D, belying their creation by meshes overlaid with images. In contrast, the perfectly-emulated cinematography of the game engine reveals a world awash in warm, dusty sunlight. This sets up a visual tension—the stylized, quasi-realistic modeling of the world is viewed through photo-realistic cinematography where light refracts just-so off polished furniture, and ghostly reflections shimmer in windows.

The play experience of Sunset operates in a middle ground of audience expectations. It is presented in a typical first-person, three-dimensional manner that suggests real-time engagement in which the player sees through the character’s eyes, and by extension, performs in-game tasks as the player. But in Sunset, the player navigates Angela to the room where the task is to be completed, and once the player locates the site of the task, she simply has to click on the appropriate space or object, and the task is complete.

Instead of transposing the act of sweeping or plunging or washing into actions performed with a game controller, the player simply clicks, at which point the view shifts to the glimmering evening sky as the clock shows time rapidly passing while the task is presumably performed off-screen. This can be read as Angela’s own focus during her chores—she tunes out and daydreams, with little active mental attention required to carry out tasks she has done over and over during her time as a housekeeper. The extra-mimetic nature of the interactivity also relocates the core play activity from performing intricate tasks to moving and seeing. In the realm of 3D games, the acts of seeing and moving are so commonplace as to not be considered game actions; in Sunset, this extra-mimetic treatment of the tasks the player is asked to perform shifts the focus of the experience from goal-completion to a more atmospheric story experience.

There are two additional “videogame easy” actions available to Sunset players—listening and examining objects. As Angela rides the elevator up to the apartment each day, she receives her list of chores, while we hear her thoughts, which tend to focus on snippets of current events relating to the war, and details from her own life and that of the apartment owner. Angela encounters various objects as she moves around the apartment—magazines, records, artworks, papers. Some of these objects trigger additional commentary by Angela, here presented as text. Angela’s verbal and written commentary become the primary vehicle for backstory and interpretation.

Despite the goal-oriented premise, Sunset is more atmospheric than mechanical, and more concerned with a sound and audio-driven story experience than goal-oriented achievement. This is a far cry from most videogames set in times of war—instead of focusing on combat, Tale of Tales looks at how a time of conflict impacts the quotidian.

Kentucky Route Zero

The second game I’d like to look at is Cardboard Computer’s Kentucky Route Zero, a game in five acts, the first three of which were released in 2013 and 2014. The game augments the traditions of the point-and-click adventure game genre with a keen cinematographic eye, while stripping away the puzzles typical of the genre. Players follow Conway, a truck driver, as he attempts to deliver antiques in the backroads of Kentucky. As was common for point-and-click adventure games, scenes are presented as deep-focus middle shots that establish context and characters, and are the stage on which scenes unfold. Moving Conway, and on occasion, other characters, is the core interactivity. Typical for the genre, this is accomplished by clicking on the place the player wants the character to move.

Much of the game’s beauty comes from its visual and cinematic style. Flatly colored, stylized figures, objects and spaces are composed from planes of geometric color, together generating a flat, two-dimensional pictorial space. The only nuance and shading comes from the lighting sources, which also provide the primary indicators of depth in the environment. Though subtle, the camera work is precise, feeling more like carefully composed cinematography than what we might expect from a point-and-click adventure game. This happens largely through the decoupling of the camera from the player, allowing a more deliberate composition, framing and movement.

The camera movement also suggests a depth in the seemingly two-dimensional world. The game is indeed three-dimensional, organized along a series of planes within a shallow stage-like space. The camera tends to track Conway’s movement and the action in general—panning left if he goes left, zooming in slightly if he moves away from the picture plane, tracking him if he moves upward. The camera movement causes parallax effects that give the game a quiet cinematic lushness.

Changes in scene are indicated by small directional prompts. The typical design decision would be to allow the player to make these changes by clicking on a door or ladder or otherwise abstract the passage from scene to scene through an in-scene interaction, like clicking on the door to indicate Conway should pass through it. But in Kentucky Route Zero, these choices are moved into super-imposed interface elements.

Similarly, there are interface prompts for three additional activity types: “look,” which provides a more detailed written description of a person, object or animal; “talk,” which opens text dialog trees; and “use,” which can mean different things depending on the item: pick up, drive, turn on, and so on. The text trees through which conversations and verbal actions occur are the source of much of the story progression. Decisions are made, situations worked through, backstory explained, and most importantly, the main through line—Conway finding his way to his delivery destination—unfolds through these conversations.

The most curious of these is “looking.” Instead of allowing the player to zoom in on a detail, something fairly commonplace for examining objects in games, players are instead given a written description. Often, the description fills gaps in the level of visual detail—letting you know a chair is a Queen Anne, or the condition of Conway’s dog’s hat. Other times, these indicate activity. These descriptions are presented parenthetically like the stage direction one might find in the script for a film or a play. These descriptions also deepen the style and tone of the game tone.

These two devices—overlaid selection menus and the use of text for description and dialog—engages the player while keeping them at arm’s length from the story and characters. We never become Conway, even if we get to decide where he walks and what he says. We are participants in establishing the tone and tenor of the game, but we are not an actor within the game.

Unlike many videogames, Kentucky Route Zero has no pretense for immersion, instead opting for absorption. Most everything about the game establishes a carefully-controlled play experience that can be like the best of film or literature—allowing the player to become absorbed by the authored experience.

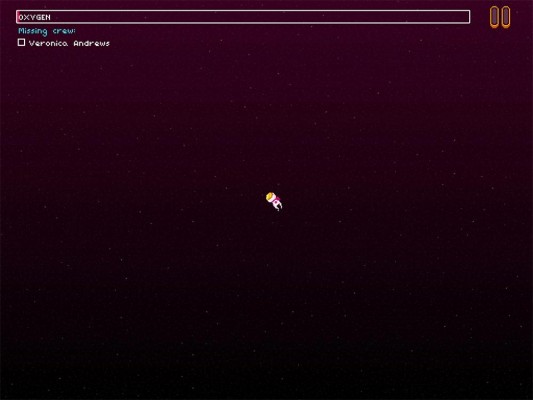

Vietnam Romance

The last game I’d like to look at is Eddo Stern’s Vietnam Romance, a game still in development, though it has been displayed on several occasions including a solo show at Postmasters in New York this past summer. The current state of the game is a series of nine vignettes, primarily constructed from the conventions of side-scrolling games—driving a car, flying a plane, shooting an arrow at a distant deer, catching objects thrown from a vehicle ahead on the road, and so on.

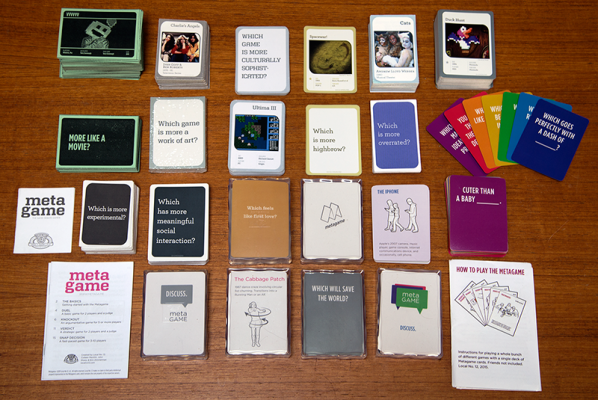

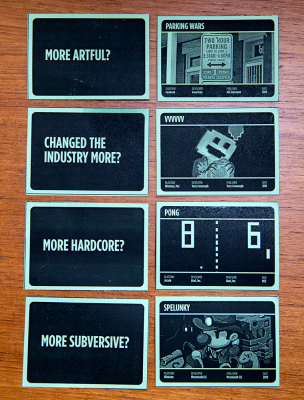

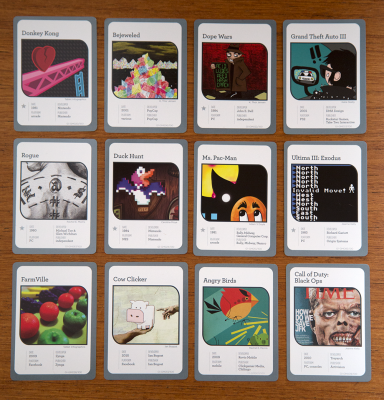

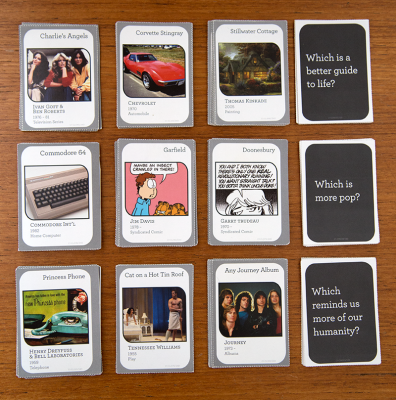

Woven through the scrolling levels is a collectible card game. The cards represent the resources necessary to carry out the actions of the game. The play experience then unfolds as the player navigates while pausing on occasion to collect, examine and “play” cards.

Early in the game, “If you hated the War but liked the Movies, you’ll love this Game!” scrolls across the screen. This seems like a glib joke, but it is key to making sense of the game. Vietnam Romance is a playable meditation on American cinema’s romanticization of the Vietnam War.

The most striking thing about Vietnam Romance is its visual style, and how it is creates the play space. The graphics are all hand-created watercolors mapped onto extruded shapes. This creates a sense of depth with the overall effect of watercolors affixed to black foam core arranged on flat planes receding into the middle distance. The clearly hand-made style created from saturated colors create a striking play experience that feels less like a videogame than a playable diorama.

It may well have been easier for Stern to use a more realistic, three-dimensional style, but that would have likely led to the game reading as a typical war simulation. And so the watercolored diorama creates a necessary distance, allowing us to consider a different aspect of war.

Similarly, the move away from first-person aiming and shooting or the strategic deployment of military forces are set aside for set pieces inspired by films like The Deer Hunter, Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now and the Vietnam War tourism phenomenon.

The activities in these set pieces vary widely—puppeteering a Nancy Sinatra-meets Full Metal Jacket dancer; taking an aging Rambo-esque fellow deer hunting; catching playing cards thrown from a ox-drawn cart; shooting letters out of karaoke lyrics, and so on.

The curious thing about some of the set pieces is their pressure on player skill. Many require a mastery of videogame actions. For example, the opening driving scene becomes a resource management puzzle to keep the beaten up car from overheating, while the deer hunting scene demands a keen spatial understanding coupled with precise trajectory calculation. These are akin to carnival games, as they test the player’s skill, but ultimately do not thwart the overall play experience—the player can simply give up, and resume the vignette, or return to the menu to play a different vignette. The game becomes an amusement park cars-on-a-track ride exploration of videogames and American cinema as much as it is a look at Vietnam War nostalgia.

Challenges for an inclusive aesthetics

Looking at these three games, we see different approaches to bending and breaking videogame genre expectations to create expressive play experiences that largely stay away from goal achievement and systems-driven interactivity. This presents a challenge for analysis and critique: if these games meld sound, image, story and repurposed game tropes to construct play experiences, but ignore most all other expectations of videogames, can we still evaluate them using the critical language of videogames?

Even at their most inclusive, the theoretical frameworks of game studies and digital media can fall short. Take Janet Murray’s defining characteristics of the digital medium: procedural, participatory, encyclopedic and spatial. As Murray’s theory is generally interpreted and applied, the presumption is that videogames should push these properties to their logical extensions, meaning player interaction should lead to unexpected outcomes within the designed space of possibility. Sunset, Kentucky Route Zero and Vietnam Romance are indeed inside Murray’s boundaries, but they use the digital medium and videogame tropes for authorial expression that is light on interactivity as authorial agency.

This leads to the consideration of the importance placed on choice and decision-making. The concept of meaningful choices has long stood as a defining principle of game design. This perspective is best embodied in game designer Sid Meier’s definition of a game: “A game is a series of interesting choices.” which places value on players having an active role in determining the outcome of the game. From this vantage, Sunset, Kentucky Route Zero and to a lesser degree, Vietnam Romance, fall short, as there is a presumption that interesting choices give players systemic impact on the quality and quantity of the play experience.

This points to the value placed on games as dynamic systems. Videogames are approached as interactive systems within which players can tinker and pursue measurable outcomes. In these three examples, the systems dynamics tropes are for the most part replaced with structures of progression rather than emergence, to borrow Jesper Juul’s terms. For these games on the margins, it is necessary to see the systemic confluence of visual and aural elements, interactivity and theme and not just on state changes.

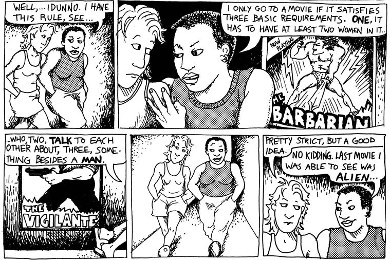

This suggests another early theoretical framework—Espen Aarseth’s nearly 20 year old theory of ergodicity. As Aarseth defines the term, “… nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text.” Aarseth’s example of trivial traversal is the act of reading a book—assuming one knows how to read, and is familiar with a given culture’s conventions for navigating pages and their sequencing, reading requires minimal effort, and thus is non-ergodic. Aarseth’s ergodicity has been broadly interpreted to speak to the player’s agency in shaping the game text through in-game actions. But in games like Sunset and Kentucky Route Zero, player actions are mostly the equivalent of reading and page-turning, at least from a vantage that privileges meaningful choices within a systems-driven space of possibility.

The reception and literacy side of these experimental works cannot be taken for granted, however. Each of these three games make demands on players that at once requires gameplay literacies and an openness for experiences partially outside videogame conventions. Tale of Tales’ Sunset asks us to understand and master the basic interface of a 3D first person videogame—look and walk. For gameplayers, these have become trivial, but for those who might have more affinity for the subject matter but aren’t gameplayers, this basic expectation is a barrier. Vietnam Romance is also instructive here—the deer hunter / Rambo vignette requires a surprisingly sophisticated ability to estimate distance and trajectory across a long distance. We find a tension point here for developing more inclusive critical frameworks—one player’s nontrivial is an another player’s rote and commonplace.

If we re-orient our focus toward a more experiential set of player choices, the real value of these games becomes clear. Aarseth uses labyrinths and mazes to tease out the differences between ergodic and non-ergodic literature. Unicursal labyrinths involve movement through an ultimately linear path absent of decision points. Multicursal mazes require decisions at forks in the path which have a substantial impact on where the experience goes. The presumption is most ergodic texts are multicursal. In our three examples, they generally don’t present multicursal “meaningful choices” that drive toward goal completion or quantifiable outcomes with win and lose states.

But if we shift this from a valuation of a player’s exploration of a space of possibility to the experiential choices a player makes—peer out the window at the city sky, pat a dog’s head, wonder at amusements from a slowly moving car—these games present meaningful experiential choices within a unicursal play experience. Analyzing and critiquing games like Sunset, Kentucky Route Zero and Vietnam Romance requires we break from the systems-driven, goal-oriented evaluation of player activity. The roles of player agency and decision-making have to be re-located to support the value of lighter player impact and heightened authorial expression.

At this stage in this project, I’ve only scratched the surface in sketching out the issues in creating an aesthetic framework that values experiential play experiences, and I am raising more questions than I’m answering. Hopefully, though, I’m starting to reveal a path toward a more inclusive videogame aesthetics.